"Brother Orange" is finally out 🍊

My husband's been making this doc for 10 years so I interviewed him about it

I will be donating all January proceeds (plus extra) to the Pasadena Humane Society who helped rescue hundreds of animals in the Eaton fires. You can, of course, feel free not to upgrade your subscription and donate directly.

Abe and I met at Wesleyan our junior year, and spent most of our senior year in the film studies building together. I wasn’t a Film major but Abe was, and he needed to be by the flatbed machine so he could cut his senior thesis film. Like, literally cut it. This was before digital editing, where filmmakers physically spliced/taped together film. So I spent many months in that room next to him, writing my own senior essay (about Fanny Mendelssohn, Felix’s sister) for my Women’s Studies/Music major.

Fast forward several decades, and we now we each have a feature film directing credit under our belts. Abe’s documentary “Brother Orange” premiered yesterday on VOD and I thought it’d be fun to interview him about it, since I basically lived the ten-year journey alongside him. I hope you rent/buy it (Amazon, Fandango, Apple TV) and enjoy our discussion below.

So I Married a Filmmaker

LYNN: Well, Abe Forman-Greenwald, thank you so much for taking the time to sit on this couch with me.

ABE: You're very welcome… uh, I mean, thanks for having me.

LYNN: We're off to a great start here. Okay, so since we have been together for several decades and I have been with you pretty much throughout every step of this documentary, I decided to consult an AI system about what questions might be good to ask you. And I just wanted to let you know that it said that “Interviewing your husband about a documentary he's been working on for a decade is an exciting opportunity!” And I do think that that is true because I get to ask you questions nobody else gets to ask you, about the making of this movie. So why don't we start with the title and, what this movie is about for everyone who is reading?

ABE: The title of the documentary is “Brother Orange.” It is about a BuzzFeed story that was posted in early 2015 about a BuzzFeed writer who had a strange thing happen to him. His phone had been lost at a bar in New York the year before. Someone had come in and taken it off the table. And then he went out and got a new phone, didn't really think about that again until a year later – when photos started popping up in his photo stream that he didn't take. They were photos of storefronts and streetscapes somewhere that looked like it was Asia and he was a bit freaked out by this, but also curious. So he wrote a post for BuzzFeed called “Who is This Man and Why Are His Pictures Showing Up On My Phone.” That post was then translated into Chinese and went super viral on Chinese Twitter, which is an app called Weibo. The Chinese internet found this man within a day. The Chinese Internet dubbed him “Brother Orange” because he had taken all these selfies in front of an orange tree. Those were some of the photos that popped up on Matt's phone from BuzzFeed.

LYNN: Wait, I don't know if you said his name.

ABE: Yes. Thank you. The reporter's name is Matt Stopera. He's a longtime BuzzFeed writer. He wrote the first ever BuzzFeed list, and he's covered celebrity and pop culture. But now all of a sudden, he is the focus of this bizarre story, and he's become a meme in China. So this man, Brother Orange in Southern China, invites Matt in New York to come and visit him at the restaurant that he runs, which is in a smaller city in southern China. Matt decided to go and just trusts that everything would be okay, even though this all came together in just a couple of weeks. So that's a long way of saying that it's a story of an unlikely friendship started on the internet, and how people from different cultures can unexpectedly come together.

LYNN: You said that it's an unlikely friendship that started on the internet, which I think a lot of people can wrap their heads around, in this day and age – of two people meeting virtually. But what makes this story so unique is that it was almost like they were set up by the internet?

ABE: In a way, yes, it was a glitch that I've since learned is not completely uncommon, which is two people's iCloud being linked. I think it's often when a phone is stolen, but I've heard since making the documentary that this has happened to other people, where photos that they didn't take pictures of started showing up in their photo stream. But the unique part of this occurrence was that Matt happened to work for BuzzFeed. So he posted the photos and wrote about his experience giving him a platform that other people wouldn't have, and that was how it made its way to China and became a huge, international human interest story at the time, which was 2015.

LYNN: Yes. I remember, you at the time were in the video department at BuzzFeed and you did not know Matt because he was in New York City, working in a completely different department as you. And when you heard about this story, I remember you getting very excited about it and thinking… Well, why don't you tell me what you thought?

ABE: When I first saw Matt's post, it just immediately appealed to me, and I saw the potential for this to be more than just a BuzzFeed post. There's something so appealing in this story of finding someone across the world through this random happenstance. But I was excited about it because of my love for travel and this chance to go to a place that I've never been.

LYNN: At the time you were making BuzzFeed videos.

ABE: Yeah, I was making short documentaries for BuzzFeed. So in a way, it was a natural extension of that where I had been doing kind of. Short profiles or, you know, like 3 to 4 minute short docs for BuzzFeed, and the idea to do something that was longform did not fit into my mandate, but I just saw this story as something that needed to be covered by BuzzFeed and I had more documentary experience, I think, than most people there. So I emailed Matt pretty quickly and said, “If you're going to China, I want to come too. This would be a great documentary.” And that was the start of both the project and a long term friendship with Matt and Brother Orange.

LYNN: So for those who don't know, most documentaries – even though a lot of them are very low budget or they're mostly passion projects – usually have more than one person working on the crew. There's usually a sound person. Sometimes there's a producer there to help fix things or make clearances. But this was literally just you and Matt and Brother Orange. And I want to know a little bit more about what made you feel confident that you could do this in a long form way. I mean, most people have people there to back up files and make sure they have enough battery power – all these logistics that are required usually to make a feature. And you did not have that. So I'm just wondering what gave you the confidence to do that? Also tell me about your filmmaking strategy, if you had any? In terms of like checklists and, and trying to make that happen because most people would not have the confidence to do that.

ABE: Yeah. For me it wasn't that. I didn't really think strategically. I just thought, I guess, opportunistically. This would be an amazing adventure. I would be able to go through my job and go to China, where I've never been, and get to see firsthand this very unusual story that, like I said, appealed to me immediately. And in terms of my documentary inspirations, the idea of a one person or two person crew wasn't intimidating to me because two of my favorite documentary filmmakers are Ross McElwee, who is a one person operation. Films and records all sound by himself, and is also a character in his films, which I'm not really in this one. And the Maysles brothers, who filmed and recorded their own projects. To me, I love verité documentaries, and this was the way to undertake a verité documentary. And I knew that it was unlikely they would even send me to China to do this, let alone another person. And that was indeed the case. BuzzFeed video was always a “scrappy” operation. The ethos was to use a very low budget, but a compelling concept to reach a wide audience. And I tried to take that with me in this approach. But again, it wasn't strategic so much as this was the way to do it. It was me, my camera, shotgun mic mounted on the camera, and no lights. And no tripod. Everything was handheld, run-and-gun, which was necessary for the story. We didn't even realize the scope or the speed of what was going to be happening. Once we got there, we thought – we didn't really know what to expect, really, me and Matt. And so I flew to New York, followed Matt as he packed up his things and went to China, basically on a leap of faith. And when we got there, there was a ton of Chinese media following Matt and Brother Orange for several days as we went on a tour of his local area, which is in Guangdong province.

LYNN: Which brings us to China. Now…

ABE: Wait, can I say one more thing about my documentary inspirations?

LYNN: Of course.

ABE: One of my first jobs out of college was working as an editor on a series of fundraising trailers for a documentary called “Kings Park,” which was directed by Lucy Winer, who really was a documentary mentor for me. So many things that I love about documentaries I learned from her, and I just wanted to have that included how much that education meant to me. Because I didn't study documentary at all as an undergraduate.

LYNN: Right. At Wesleyan, where we met, you were a narrative filmmaker.

ABE: Filmmaker is generous.

LYNN: Well, you did make two shorts, and I was very impressed by them, because I wanted to be an actor and I was hoping you would cast me to be in one. So I was wondering how you felt about –

ABE: About not casting you in my thesis film in 1998?

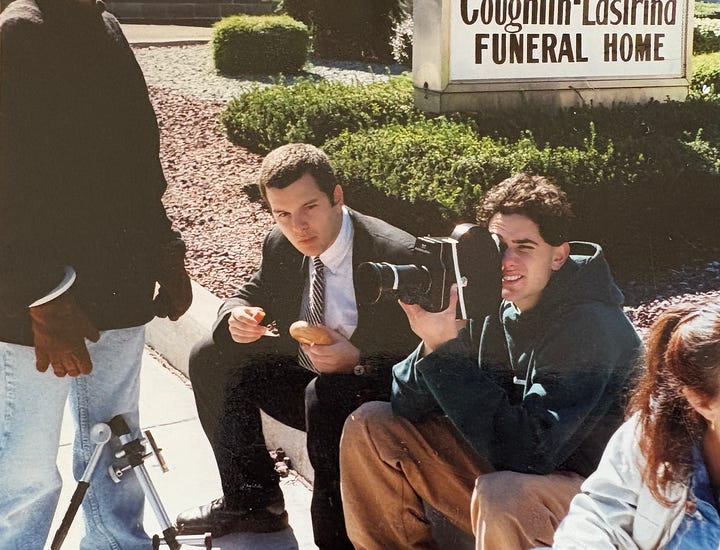

LYNN: No, that wouldn't even have made sense to cast me in that film – but no, that wasn’t going to be my question for you. My question for you was, how do you feel about me becoming a narrative filmmaker and you becoming a documentary one? I don't think either of us thought that was going to happen when we were sitting at the edit bay in 1997, and you were cutting your short film, “King of Carversville” on a flatbed.

ABE: Yeah, that's true. In college, I never really thought about being a documentary filmmaker. And I mean, I don't know that I do much now either. This is really the only feature documentary that I've made. I love it. I think I've learned a lot through the process.

LYNN: You made “Geeks on Board.”

ABE: I did that, but that didn't really get a release, so this would be my only documentary that I've made that is getting any kind of wide release.

LYNN: So you consider this your debut, your feature debut?

ABE: Yes. Okay. What do I think about you being a narrative/me being a documentary filmmaker? I think it's great. And I think it suits both of our skills. Well, I think you have an incredible level of organization.

LYNN: Yeah, I couldn't do the run-and-gun by myself thing.

ABE: You are a great motivating leader of a group. And I was extremely proud of you. And watching you work on set? I think the way that you approached that was just something that I had a lot of pride and admiration for you, and it's obviously a very different thing than doing a one person operation.

LYNN: Well, if I may return the compliment, I said, I don't think I could ever do that one person thing just now, but that's not true. I do a lot of short form videos on YouTube, and so I do those by myself, and I have to say that so much of that has come from not only having the confidence using your cameras, but also, you've helped teach me how to edit.

ABE: That’s just because I got tired of editing for you.

LYNN: Well, yeah, that's very true.

ABE: No, I'm also impressed with the evolution of your editing skills. You've come a long way.

LYNN: It's true. I have come a long way on Adobe Premiere Pro, but that said, I think for filmmakers, especially those of us who did not go to film school, sometimes it's just about feeling like you have a support system. Even if that person isn't hovering over you, telling you what to do, it's just like – if you see it, you can believe in that creative way of life. And I think even just seeing, you know, no lights, I mean, that is a huge thing because most people think –

ABE: I don't know lighting.

LYNN: Yeah, exactly. Me seeing you, with the lack of lighting.

ABE: Oh. NO lights, zero lights. I thought you meant “KNOW lights” like K-N-O-W. Lack of lighting, that’s laziness.

LYNN: Maybe, but still being able to create a beautiful product and having that be okay. Also even like, seeing how you use a shotgun mic and you rarely use a lav mic.Y

ABE: Yeah. I don't like the way it looks, especially for a verité thing. I like to keep the frame as clear as possible of any kind of artifice. I guess that sounds so pretentious, but I think it's very distracting. I think it’s my reference as a viewer. When I see – I'm going to sound like an old cranky person, but I don't care – when I see, like on YouTube, someone holding the little Rode wireless mic –

LYNN: Turning the audio into a prop?

ABE: I guess. Having visible markers, visible reminders of the fact that this isn't just life being documented. For me as a viewer, it takes me out of something that I want to be immersed in the experience.

LYNN: It's almost like a news reporter?

ABE: Yeah. I guess. And again, I'm not saying anything is right or wrong. I'm just saying that for me as a viewer, I don't like to be reminded that there is someone making this thing. I like the idea that I'm watching life unfold. And those visual things can take me out of it. That's part of the handheld aesthetic that I like. It's part of using a shotgun mic rather than a visible lav. And this all might just be to justify my own laziness. I don't know, I don’t like to do all that prep. But I think for “Brother Orange” specifically, this was all by necessity. I went to China alone with a Canon 5D and a mic mounted on top of it. And I did have audio issues – one of the audio channels went out. And I had to kind of mess with all of that. Luckily I didn't actually lose any audio fully. But it was stressful when I was on the ground there because I was far from any major city, so there wasn't really any technical assistance possible. So there would be lunches where I'd be out in the car trying to figure out the audio.

LYNN: Let's talk about China because this was your first time there and you were not there with your Chinese wife.

ABE: I have a Chinese wife?

LYNN: You have a Chinese-American wife. So, what did that feel like?

ABE: Well, the one thing that I learned after I was in China was that the area I was filming Brother Orange was actually pretty close to where my mother-in-law had lived. That's your mother, Lynn.

LYNN: That's my mom.

ABE: Where she had lived when she was a little girl. And partly I was embarrassed by how little I knew about Chinese culture, including the fact that there's this large ethnic group of Hakka people. Brother Orange is Hakka, the region where I was – Meizhou – is considered the heart of Hakka culture, and I had never heard of Hakka. Didn't know anything about it. And then once I got back, talked to my mother-in-law and learned that she was Hakka and spoke Hakka? It was a really moving experience to have her speak with Brother Orange in Hakka. When he ended up coming to the USA. But being in China was… it was amazing. It was very different from any place I've ever visited. I've always been curious about it, and I think I got to see this part of the country that most tourists don't go to. And it was really illuminating. Another part of Hakka culture is that people are very welcoming to guests, and both me and Matt really felt that when we were there. I've never been welcomed like that by strangers anywhere in the world.

LYNN: And when you were in China, was there a moment where you were scared? Not really in danger, but more… nervous about the government aspect? Did you ever find yourself asking yourself, “What am I doing here Why am I doing this?”

ABE: It mostly felt magical. I mean, there's some paranoia. I would say it was more in anticipation of going because we didn't have work visas. We went on tourist visas and because this whole thing happened so quickly, there wasn't time for a work visa. And I'm not sure we would have been approved for one. But it turned out that the local government was supportive of us being there, so that wasn't really an issue. And then I felt a lot better about it, once the story was covered on CCTV, which was the national news station there, that gave me the comfort that this story was kind of approved by the government. And that will not be an issue for me. But yes, most people would have had a “fixer.” They would have had a lot more support in place before going. But part of the nature of what this was was that it had to happen really quickly. So I was very anxious ahead of time, but once I was there, I didn't feel like I was in danger.

LYNN: So the first part of the documentary takes place in China, and then the second half takes place in America. And how were those two circumstances different and how are they similar?

ABE: They felt different in that the attention on the story was much greater in China than it was in the US for a variety of reasons. I think partly the story had spread so widely in China because it had happened during Lunar New Year, when the country kind of shuts down and everybody returns to their hometown and they have a lot more time on their hands. So that's when it went super viral. So many people were aware of it, and the numbers on Weibo were astounding. It was like 75 million views of different posts. It was just massive, and everywhere we went, people knew who Matt was. People knew who Brother Orange was – certainly in Meizhou where Brother Orange lives. But even when we went to Beijing at the end of our trip there, people would recognize them in Beijing. So it was much more of a media spotlight on them in China in a way that it wasn't in the US. It was also this media company in China that took the lead in making this whole itinerary for Matt and Brother Orange, and we didn't have that in the US. So it was me and Matt kind of coming up with an itinerary on the day over here. So it's a much smaller scale operation in the States. The similarities, which to me were really sweet, were just this desire on both of their parts to show one another their home, their family and their culture. And that was really special. Matt had never been to China before, and Brother Orange had never even left his country, let alone come to the US. So there was a lot of exposure to new things for both of them, which was really cool to see firsthand.

LYNN: I don't want to give a spoiler, but since you can see her very quickly in the trailer, what was it like meeting Britney Spears? Did you imagine when you were initially doing this, that it would lead to that kind of experience?

ABE: No, that was totally unexpected. I did a little bit of research on Matt right before I started filming with him. And of course, one of the first things that I saw about him was that he is a massive Britney Spears fan. He's written tons of posts about her. He had been on MTV talking about her when he was in middle school. He's obsessed with her. And once we got to the US and they were on the Ellen show, I think Britney's team and Planet Hollywood invited them to come to her concert. So I knew it would be a huge deal for Matt, and seeing him get to dance with her on stage… it just seemed like he was transported out of his body. It was a long series of incredible things that were happening. An amazing thing to see, especially since three weeks before, he had been teaching Brother Orange Britney songs in a tea field in China.

LYNN: I'm going to go straight to the AI questions now… let’s see… hmmm, I think I asked better questions than this program did. Okay I will ask you this, as our last one: “Now that the documentary is complete, what's next for you as a filmmaker and what do you hope to accomplish in your future projects?”

ABE: I don't have any documentary projects in pre-production. I don't have a list of topics that I would like to cover. My ideal follow up to this would be a story that I’d come across in a similar way – which is just seeing some kind of remarkable, unlikely story, finding someone who's a willing participant to let me come along on that journey and following it to see where it leads. I hope that it won't take another decade to go from start to finish. But you know what? In documentaries it is not that unusual, and you know… a love for making verité documentaries means you don't know how it's going to start or end. So you have to just kind of take a leap like Matt did in going to China and hope that something comes out of it. And I don't think I'll ever have an experience like this again. But that would be the way that a future project might come about.

LYNN: Well, thank you so much for taking this time to sit with me on our couch and pet our dog and reminisce about your life as a filmmaker – as a documentary filmmaker – and the making of Brother Orange, which comes out January 21st.

ABE: No further questions?

LYNN: No other questions. Thank you.

ABE: Well, thank you for this opportunity, Lynn.

LYNN: You're welcome, Abe.